What color should rear turn signals be? In North America they’re usually red, and can also be amber. Almost everywhere else in the world, they have to be amber.

Khodrocar - Traffic moves and changes quickly. Fractions of a second make the difference between a crash and a miss. That means that clear, unambiguous brake and turn signals must convey their message without requiring any unnecessary decoding — as in, a red light = brakes and amber = turn.

Amber wins over red even without the less dramatic niceties: in traffic, drivers looking well ahead can make better decisions about lane changes; traffic congestion is reduced. But safety regulations aren’t based on common sense; they’re supposed to be based on evidence, facts, and science. So what are the facts?

In 2008, NHTSA (the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, responsible for writing U.S. vehicle safety standards) released tentative findings that amber ("yellow”) turn signals are up to 28% more effective at avoiding crashes than red ones. Then, in 2009, they released preliminary findings that across all situations, including those in which turn signals don’t matter, vehicles with amber rear turn signals are 5.3% less likely to be hit from behind than otherwise-identical vehicles with red ones.

That means amber turn signals were seen as being more effective at avoiding crashes than the center third brake light (CHMSL) mandated in 1986 (with a 4.3% crash avoidance).

Those are important first steps, but the slow pace and lack of action is frustrating. This isn’t unknown territory, an unproven new technology, or even an expensive proposition. Amber rear signals are required in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Asia (including Japan, China, and Korea), South Africa, and most of South America.

Outside North America, red turn signals have been banned almost everywhere for 35 to 55 years.

There has been support for amber signals in America since the 1960s; indeed, in 1963, amber front turn signals replaced white ones, because amber is quickly separated from white headlights and reflections of sunlight off chrome. But automakers rejected amber rear signals as "not cost effective.” Volkswagen’s 1977 study concluded amber rear signals are better—but now they use red ones on their American cars.

Fifteen years ago the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, one of the world’s most respected vehicle safety research outfits, determined that following drivers react significantly faster and more accurately to the stop lamps of a vehicle with amber rear signals versus red.

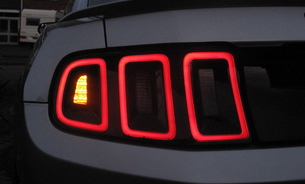

American regulators, alone in the world, have dismissed the idea that there might be something wrong with trying to convey two very different messages with two (or just one!) identical red lights. So automakers play "now it’s amber, now it’s red” with rear turn signal color in the American market: amber this year, red next year, back to amber at the next facelift. Even imports have red rear signals in America, sometime because stylists will use any tool at their disposal to differentiate this year’s model from last year’s.

Stylists don’t deserve all the blame. In America, the brake light and rear turn signal must each have a lit lens area of at least 50 cm2 (7¾ in2). The American regulation calls this lit lens area "EPLLA” for Effective Projected Luminous Lens Area. This minimum-size requirement doesn’t exist outside America. It’s not such a big deal on a large vehicle where there’s plenty of space for a large rear lamp, but on smaller rear lamps space is at a premium. There often isn’t room for two lamps of at least 50 cm2, so that makes a design constraint.

American regs say rear turn signals can be implemented by flashing the brake light, so the automaker needs to have only one lamp of at least 50 cm2 per side. Problem solved; the red combination brake/tail/turn lamp is legal. But should it be? Is it good enough?

It has the safety drawback of red instead of amber. And with a combination lamp, a driver braking and signaling at the same time shows other drivers only two-thirds of a full brake light indication. A driver getting on and off the brakes while the turn signal’s on creates a confusing mess of flashing red lights, and a faulty lamp takes out two crash-avoidance light functions instead of just one.

So it’s a plus-one, minus-one situation; America gets along without the safety benefit of amber rear turn signals on all vehicles, and the rest of the world gets along without the safety benefit of minimum signal size requirements, right?

Well…no, actually, and here’s why: there’s a good pile of evidence that amber signals do a better job than red ones, but there’s no safety-related reason for the minimum lit-size requirement. There never has been.

The minimum size was adopted in the mid-1950s when a Society of Automotive Engineers lighting committee met in Arizona and evaluated cars with different rear lighting configurations. The engineers peered at the cars as they were driven away, then voted on which systems they thought looked okay. There were two reasons for specifying minimum lit area: the lens plastics available in the 1950s weren’t very colorfast or heatproof, and requiring a minimum lit area was a way to ensure, without design-restrictive explicit requirements, that the lens would be a minimum distance away from the hot bulb, to stave off fading and cracking.

The other reason was to do with glare and how bright a lit surface appears – the luminance of the surface. It’s not the same as intensity, which is how much light a lamp is producing. It’s intensity, not luminance, that determines how effectively a brake or signal light conveys its message to other drivers. But luminance bears consideration, too: a given amount of light can appear more glaring when it’s coming from a relatively small surface, because the light is "denser” – the luminance is higher – on the smaller surface than on a larger one. The minimum lit area requirement acts together with the maximum intensity requirement as an indirect, implicit luminance limit to turn addresses a theoretical concern that a very bright, very small brake or turn light could be too glaring when viewed at close distances. [Editor’s note: this turned out to be a problem anyway, as the US allows brake lights to be too intense. New technology (LEDs) in the absence of an actual luminance limit resulted in that glare problem.]

The last time NHTSA looked at the issue, in 1993, they found no evidence that a 50-cm2 lamp is any more effective at preventing crashes than a smaller lamp of the same intensity. NHTSA also found no evidence of a glare problem with relatively small signal lights, because a smaller lamp’s higher luminance and lower intensity balanced out pretty well with a larger lamp’s lower luminance and higher intensity. So why didn’t they change it?

"We don’t find any dispositive reason to keep the requirement, but we also don’t find any dispositive reason to eliminate it,” concluded NHTSA’s report. So they kept it. That was before NHTSA’s own good evidence saying amber signals work better. Maybe now there’s a reason!

At that time, LEDs were not yet used in primary car lights; brake and signal lights all had the familiar incandescent bulbs. And the light-dispersing surface was the lens itself, which had optical patterns on its inside surface to distribute the bulb’s light collected and amplified by the reflector. This meant the whole lens area where light was traveling through was…lit! From any viewing angle and any distance, the entire lens area appeared luminous.

Then came more advanced optics, giving us crystal-clear lenses; optics were moved to the reflector to create a jewel-like appearance. No longer was the whole lens lit, but instead at close distances we see very bright spots and lines of light surrounded by dark bands and spaces. The same is true with many LED lights, which show bright dots surrounded by dark spaces. LEDs with small total area can produce high intensities that would require much larger area with a bulb-and-reflector setup. With these changes, the minimum lit area requirement no longer has any relation to the luminance or intensity produced by a car light. It’s an obsolete requirement that now stands in the way of the real safety improvement we could have if all vehicles had amber rear turn signals.

Suppose tomorrow someone waves a magic wand and the EPLLA size requirement vanishes. Automakers still like the styling freedom to choose the turn-signal color, amber or red. So we can solve most of the problem by getting rid of combination brake/turn lights, right? Well…no. All we do is exchange one set of problems for another.

With separate red brake and turn signals we have identical – and dueling – red lights right next to each other. If the driver of a Golf, Jetta, Passat, Sonata, X5, Q5, Accord coupe, or any other car with red turn signals right next to the brake lights is braking and signaling at the same time, the turn signal is practically invisible until the car behind is about to drive up the tailpipe. And here again, if the driver’s getting on and off the brake while signaling, just forget about unscrambling a coherent message from the mess of flashing red lights in the fractional moment available at speed in traffic.

Some of the problem goes away if the two identical red lights, the brake light and the turn signal, are widely separated from each other. It’s instructive to look at the ECE regulations, used just about everywhere but in North America. They don’t allow red rear turn signals, but they do require two bright red lights in the back: the brake light and the rear fog light, an extra-bright tail light activated by the driver when it’s foggy, so following drivers can still see the car. They look similar to each other, just like the American red brake and red turn signal, so the ECE regulations say their closest lit edges have to be at least 10 cm (4 inches) apart. That way, drivers have no problem seeing and discerning both functions. But there’s no such separation requirement for brake lights and red turn signals in American regulations.

Even with the lit-size requirement, amber rear signals have never been really tricky or costly or difficult. American cars were being sent to Australia with amber rear signals back when Ward and June were scolding Beaver Cleaver for leaving his bike in the rain. Countries like Australia accommodated U.S. cars by allowing reversing lights to be amber or white: signal for a parallel-parking job, shift to reverse, and one amber light burned steadily while the one on the signal side flashed. Meanwhile, both red brake lights lit steadily.

It was not a bad solution; in America we have amber or white front parking lights and amber or white daytime running lights, so everyone in America knows that a pair of steady amber lights means you’re looking at the approaching end of the vehicle. The reversing light is a secondary, seldom-used light function, so there’s much less consequence of piggybacking it onto the turn signals than piggybacking the brake and turn lights. Today’s amber turn signals are often bigger and brighter than tiny, dim white reversing lights.

Even without that kind of a change, it’s hard to think of any actual car designs that lack ample space for big-enough, bright-enough, good-looking red brake and tail lights, amber turn signals, white reverse lights, and perhaps red rear fog light functions. All it takes is a sensibly written regulation in line with the science, evidence, and facts. We don’t have that right now.

Canada has long wanted to mandate amber lights, but is handcuffed to U.S. regulations by the threat of free-trade court action. There was an international effort to develop a single global lighting equipment standard based on best practices worldwide, saving money and improving safety; there would have been one standard to which an automaker could build and have a vehicle acceptable throughout the world, but if an automaker still wanted to build to specific national standards, that would have remained legal (in those countries). The effort was killed by U.S. insistence that the rest of the world would have to roll back their regulations to the 1950s and accept red rear signals. So much for "best practices!”

Shortly after releasing their tentative and preliminary 2008-09 findings, NHTSA opened a public docket requesting comment on the matter. Naturally, there are opinions on both sides. But it’s interesting to see how many ordinary drivers, with no ulterior motive or axe to grind, strongly urged NHTSA to please require amber signals.

Perhaps it’s time to think about taking a deep breath and moving the American turn signal regulation boldly into line with what the rest of the world has known since before the Beatles.

Source: ACarPlace.com

Latest News